and in the police courts:

Prior to 1848, philanthropic concern for the workers, even on the part of the government. Since 1848 progress; people realise that only a revolution can achieve decisive results here and therefore leave matters alone. Interest on the national debt amounted to 63 million in 1814, now it amounts to 271 million. In 1802 the budget was 589 million, in 1848 it was 1,692 million, an increase which cannot be explained by the stupidity and wickedness of the governments. Between 1830 and 1848 the total salaries of officials rose by 65 million. Ditto. (In France there are 568,365 officials; taking this as the basis Proudhon calculates that every ninth man lives at the expense of the budget, that is to say that there are only 5,115,285 men in France, whereas over 6½ million voted in 1848!) (p. 62). This increase in the number of officials and in the size of the military budget is proof of the growing need to enhance the repressive power, and hence of the growing danger to the -state from the proletariat[l]. This tendency of the state to maintain big landownership and capital leads directly to corruption, which is the direct consequence of all centralisation. Hence: "there is sufficient reason for revolution in the nineteenth century". This second essay contains among other things also the following gems: 1. "The system of taxation at present in force ... is conceived in such a way that the producer pays everything, the capitalist nothing. In fact, even when the latter is entered for a particular sum in the book of the tax collector, or when he pays the dues laid down by the Exchequer on articles of consumption, it is clear that his income, being derived exclusively from the prelibation of his capital and not from the exchange of his products, this income remains free from tax, since only he who produces pays" (p. 65). This last "since" says the same as the first proposition which has to be proved, and this proposition is thus of course proved. C'est là la logique tranchante de M. Proudhon[m]. This is expounded further: "There is therefore a pact between capital and the authorities for ensuring that taxes are paid exclusively by the worker, and the secret of this pact consists simply, as I have said, in imposing taxes on products instead of on capital. By means of this dissimulation, the capitalist property-owner appears to be paying for his lands, for his house, for his chattels, for the alterations he makes, for his travels, for his consumption, like all the other citizens. Moreover, he says that his income, which without the tax would be 3,000, 6,000, 10,000 or 20,000 francs, is, thanks to the tax, not more than 2,500, 4,500, 8,000 or 15,000 francs. And on top of that he protests more indignantly than his tenants against the size of the budget. Sheer equivocaton! The capitalist does not pay anything, the government shares with him, that is all." (It shares also with the producer when it takes part of his products from him, and the capitalist likewise, dicitur potest[n], shares with the producer.) "They make common cause." (O Stirner!) "What worker then would not regard himself as lucky to be written down in the public ledger for 2,000 francs of rent on the sole condition of parting with one quarter of it as amortisation?"!!! (pp. 65-66). 2) The register is drawn up "as if the purpose of the legislator[o] was to re-establish the inalienability of real estate—as if he continually wanted to remind the bondsman freed during the night of August 4 that his position was. that of a serf, that it was not his lot to own the soil, that every cultivator was of right, except through a concession from the sovereign, a tenant by emphyteusis and in mort-main!" (p. 66). O Stirner! As if the registration did not affect big real estate just as much as small, according to which Louis Philippe himself was a bondsman. 3) The theory of free trade and explanation of protective duties. The duties yield 160 million to the state. Suppose the customs were abolished and foreign competition were strong in the French market; "suppose then the state makes the following proposal to the French industrialists: which do you prefer for safeguarding your interests: to pay me 160 million or to receive them? Do you think the industrialists would choose the first alternative? It is precisely this that the government imposes on them. To the ordinary expenses we have to pay on products from abroad and on those we send there, the state adds 160 million which serve it as a sort of premium; that is the meaning of customs" (pp. 68-69). If considering the lunatic French tariff, such nonsense can be excused, it is still a bit steep that M. Proudhon measures protective tariffs in general by the French scale and makes out that they are a tax on manufacturers. 4) pp. 73, 74. Proudhon quotes a speech by Royer-Collard in the Chamber of Deputies; the debate of January 19-24, 1822[346], in which this lawyer expresses his regret at the disappearance of the independent Benches (parliaments)[347] and other "democratic institutions", "powerful assemblages of private rights, true republics in the monarchy" ; they had set limits to sovereignty everywhere, whereas at present although the government is divided up it is unrestricted in its action. This reactionary review of the old lawyer, who cannot conceal his hatred of the administrative system, M. Proudhon mistakenly regards as social-revolutionary; "what Royer-Collard said about the monarchy of 1814 is true, what he says of the Republic of 1848 is still more so." What leads M. Proudhon astray is the confused statement by Royer-Collard: "The Charter[348], therefore, at one and the same time has to provide the constitutional basis for government and society; no doubt society has not been forgotten or neglected, but postponed." What Royer-Collard understands by society is evident from the fact that he says: "It is only in establishing freedom of the press as a public right that the Charter has restored society to itself" (p. 75).

Hence "society"=the governed considered in their capability of resistance to the government.

Third Essay | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

advances n-th year |

repayment mill. |

mill. |

Excess |

balance per year | |

| 1st-12th | 4,800 | 1,320 | |||

| 13th | 400 | 240 | + (1320-400) 920 | = | 1,160 |

| 14th | 400 | 260 | + 760 | = | 1,020 |

| 15th | 400 | 280 | + 620 | = | 900 |

| 16th | 400 | 300 | + 500 | = | 800 |

| 17th | 400 | 320 | + 400 | = | 720 |

| 18th | 400 | 340 | + 320 | = | 660 |

| 19th | 400 | 360 | + 260 | = | 620 |

| 20th | 400 | 380 | + 220 | = | 600 |

| 21st | 400 | 400 | + 200 | = | 600 |

| 22nd | 400 | 400 | + 200 | = | 600 |

| etc | |||||

never increasing.

That is how M. Proudhon lays the foundation for his National Mortgage Bank.

But the thing can be done even more speedily. One issues a decree stating:

"Every payment of rent for the use of a piece of real estate will make the farmer part-proprietor of it and will count as a mortgage payment by him. When the property has been entirely paid for it will be immediately taken over by the commune, which will take the place of the former owner"

(why does the new owner not immediately enter into his rights?)

"and will share with the farmer the ownership and the net product. The communes will be able to negotiate separate agreements with the owners who desire it for the redemption of the rents and the immediate repayment of the properties. In that case at the request of the communes steps shall be taken to instal (!?) the cultivators, and to delimit their properties, taking care that as far as possible the size of the area shall make up (!?) for the quality of the land, and that the rent"

(where did the annual instalments get to?)

"shall be proportional to the product. As soon as the property has been entirely paid for, all the communes of the Republic will have to reach agreement among themselves to equalise (!?) the differences in the quality of the strips of land, and also the contingencies of farming. The part of the rent due to them from the plots in their particular area will be used for this compensation and general insurance. Dating from the same period the old owners who worked themselves on their properties, will retain their title, and will be treated in the same way as the new owners, will have to pay the same rent and will be granted the same rights"

(what rights?)

"in such a way that no one is favoured by the chance of location and inheritance and that the conditions of cultivation are equal for all. (!!!!) The land tax will be abolished"

(after a new one has been put in its place!).

"The functions of the rural police will devolve on the municipal councils" (p. 228).

Colossal nonsense.

Next he explains that

"the right to the increase in value", i.e. the right of the farmer to the improvements he makes to the soil, cannot be implemented, any more than "the right to work", however popular both of these are.

A very legal and moral point of view.

Sixth Essay

"ORGANISATION OF THE ECONOMIC FORCES"

Everything is done by way of contract. I make a contract about something with my neighbour—the contract expresses My will. I can equally well make a contract with all the inhabitants of my commune, and my commune with any other, with all the other communes of the country. "I could be sure that the law thus made throughout the Republic, derived from millions of different initiatives, would never be anything other than My law" (p. 236).

O Stirner!! Hence the regime of contract is something like the following:

This is already settled by the bank through the lowering of the rate of interest to 1/2, 1/4, 1/8 per cent, and will be completed by the withdrawal of all gold and silver from circulation.

"As for personal credit"

(i.e. not based on security),

"it is not a matter that concerns the National Bank; it should be operated in the workers' companies and the industrial and agricultural societies" (pp. 237-38).

This is conceived by all socialists[358] either as property of the commune organised through association, where the peasant is an agricultural worker in an association, or as state property which is leased to peasants. The first form is "communistic", "utopian", "still-born"; if it should be seriously attempted "the peasant would be faced with the question of insurrection" (pp. 238-39). The second form, too, is inapplicable, "governmental", "feudal", "fiscal", etc. The reasons advanced in favour of it fall to the ground, for "the net product"

(i.e. the rent),

being the result of the unequal quality of the soil, belongs not to the state but to "the farmer who receives little; it is for this reason that in our plan for liquidation we have stipulated that the rent should be proportionate to the type of land so as to form a fund in order to equalise the income of the farmers and to insure the products" (p. 240).

That means everything remains as it was before, the farmer pays the rent during the first 20-30 years to the old property-owner and then to the general assurance fund, which divides it among the owners of inferior land. Thus good and bad land will have exactly the same value, or rather the same lack of value, for it is inconceivable how land then can still have any capital value. In what way this differs from payment of rent to the state especially as the communes will be at liberty to interfere in everything—is also inconceivable. And that is what Proudhon calls

"property separated from rent, liberated from its fetters and cured of its leprosy"

and believes that it has now become a pure medium of circulation (p. 242).

With the confiscation of landed property by the state, the value of the entire landed property in the country, worth 80 milliards, would be withdrawn from circulation and, as belonging to all, that is to say to no one would have to be struck from the inventory. "In any case, the collective wealth of the nation will undoubtedly neither lose nor gain; what does it matter to society whether the 80 milliards of real estate, which constitute individual fortunes, figure or do not figure in the total? But is it the same thing for the farmer in whose hands the mobilised soil once again becomes a value in circulation, money?" (p. 245).

With the system of tenure under the state, the peasant would very soon assert his right of ownership of the soil, which would be easy for him "since the peasants would always have the upper hand in France" (p. 246).

Quite correct, of course, if the lousy small-holding system, the only one that Proudhon knows, were to be retained. But then, too, in spite of Proudhon, mortgages and usury would just as quickly reappear.

"Given the facility of repayment by annual instalments, the value of a piece of real estate can be indefinitely divided, exchanged, and undergo any conceivable change, without the real estate being in the least affected. The rest is a matter of the police, and we do not have to concern ourselves with it" (pp. 246-47).

Companies of Workers"

"Agricultural labour is a kind of labour which least of all requires, or, better expressed, which rejects with the utmost vigour, the co-operative form; one has never seen peasants forming association for cultivating their fields; and one never will see it. The only relations of concord and solidarity which could exist, between farmers, the only form of centralisation of which rural industry is capable ... is that which results from the equalisation of the net product, from mutual insurance and, above all, from the abolition of rent" (!!) (p. 247).

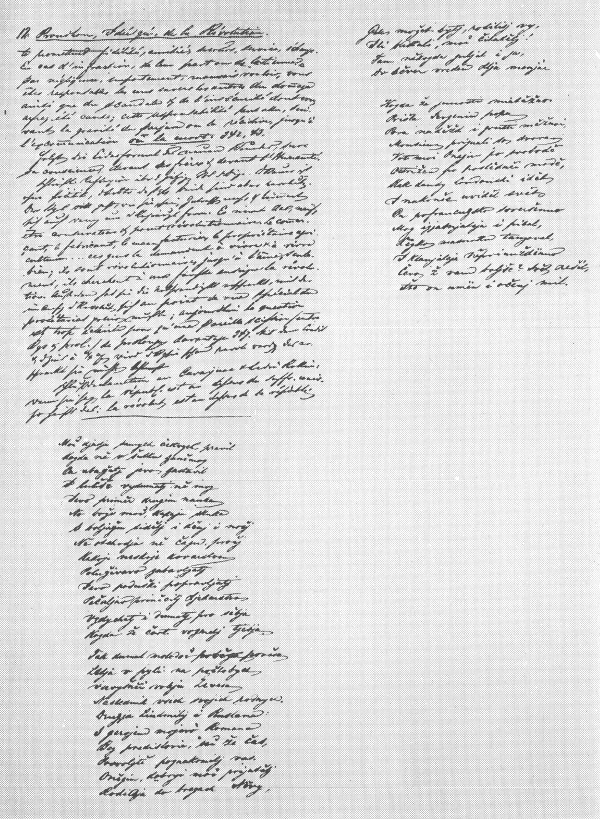

Last page of Engels' manuscript "Critical Review of the Proudon's Book

IDÉE GÉNÉRALE DE LA RÉVOLUTION AU XIX-e SIÈCLE"

It is different with the railways, mines and manufactures. Here there is either wage labour under a capitalist, or association. "Every industry, mine or enterprise which by its nature requires the combined employment of a large number of workers with different skills is bound to become the basis for an association or company of workers" (p. 249).

As regards crafts, on the other hand, "unless for reasons of particular convenience, I cannot see that there is any reason for association". Moreover, the relation of master and worker is here quite different; "of the two men, one calls himself a boss, the other a worker, but basically they are perfectly equal, perfectly free" (!!). In these circumstances, "the only purpose" of assembling a number of workers in a single workshop "where all do more or less the same thing is to multiply the product, not to contribute to its essential character by means of their diverse abilities" (p. 251).

A wretched fellow, who knows only fancy goods and the petty Parisian handicraft industry without division of labour or machinery!

Contract between society and the companies of workers:

"Vis-à-vis society, which has created it and on which it depends, the workers' company undertakes to provide the products and services demanded from it at a price that is always as close as possible to the cost of production, and to enable the public to enjoy all the improvements and refinements that are desirable. To this end the workers' company does not enter any coalition, submits itself to competition[y], puts its books and archives at the disposal of society, which retains in regard to it, as a sanction of its right of control, the power to dissolve it"

(who exercises this power?).

As to the members of the company itself:

"Every person working in the association ... possesses a joint right in the property of the company; he has the right to perform successively all duties, to occupy all posts proper to the sex, ability, age and seniority. His education, training and apprentice-ship ought therefore to he conducted in such a way that, while he is made to take his share of disagreeable and arduous tasks, he will acquire experience in various sorts of work and fields of knowledge, so that when he reaches mature age he will have a wide range of qualifications and a sufficient income. Posts are subject to election and the rules are adopted by the members of the association. The size of the recompense depends on the nature of the work, the degree of the proficiency, and the amount of responsibility. Every member of the association shares both in the profits and in the expenses of the company in proportion to his services. Everyone is free to resign from the association whenever he wishes, and therefore to settle his accounts and renounce his rights; conversely the company is entitled to recruit new members at any time" (pp. 255-57).

"The application of these principles in an era of transition would cause the bourgeois class to take the initiative and merge with the proletariat, and this ... should please every true revolutionary"(p. 257). The proletariat is lacking in brains and the bourgeoisie will readily enter into association with it. "No bourgeois who is conversant with commerce and industry and their innumerable risks would not prefer a fixed salary and an honourable employment in a workers' company to all the anxiety connected with a private enterprise" (p. 258).

(Vous les connaissez bien, M. Proudhon[z].

the Establishment of a Cheap Market"

"The fair price",

the great desideratum,

consists of 1) the costs of production, 2) the salary of the merchant, or "the compensation for the advantages which the seller forgoes by parting with the article" (p. 262). In order to secure the fair price, one must ensure that the merchant will be able to sell his goods. The Provisional Government could have made commerce flourish at once if it had guaranteed 5 per cent interest to the first 10,000 industrialists to invest up to 100,000 francs each in their business

(where are these to be obtained from, even in the highest prosperity!).

One thousand million would have been invested in industry. "Ten thousand commercial and industrial establishments could not operate simultaneously without supporting one another; what one produces another consumes; work, that is the outlet."

(The landlubber only knows of home trade[za] and like the most shallow English Tory believes that he can make large-scale industry prosper by means of it!)

Thus the state would not have had to pay 50 million, it would not have had to pay 10 million, in order to meet this guarantee (pp. 266, 267).

Worse trash never was written not even by Proudhon himself.[zb]

Contracts therefore are made on the following basis:

"The state, on behalf of the interests which it temporarily represents, and the departments and communes on behalf of their respective inhabitants ... propose to guarantee that the entrepreneurs who offer the most advantageous conditions will receive either interest"

(after payment of interest has been abolished)

"on the capital and material invested in their enterprises, or a fixed salary, or in appropriate cases a sufficient quantity of orders. In return, the tendering parties will pledge themselves to meet all consumers' requests for the goods and services they have undertaken to supply. Apart from that, full scope is left for competition. They must state the component parts of their prices, the method of delivery, the duration of their commitments, and their means of fulfilment. The tenders submitted under seal within the periods prescribed will subsequently be opened and made public 8 days, 15 days[zc] before the contracts are allocated. At the expiry of each contract, new tenders will be invited" (pp. 268, 269).

Inasmuch as the purpose of customs duties is to protect home industry, the reduction of the rate of interest, the liquidation of the national debt and private debts, the lowering of rents and leases, the determination of value, etc., will greatly decrease the costs of production of all articles and therefore make it possible to lower customs duties (p. 272).

Proudhon is in favour of abolishing. customs duties as soon as the rate of interest is reduced to 1/2 per cent or 1/4 per cent.

"If tomorrow ... the Bank of France reduced its discount rate to 1/2 per cent, interest and commission included, immediately all manufacturers and merchants of Paris and the provinces who do not have credit at the Bank would endeavour in their negotiations to obtain bills, for it would cost only 1/2 per cent [to discount] these bills received at par instead of 6, 7, 8 or 9 per cent, which money costs at the bankers" (!!!!) "...Those abroad would also have recourse to this. French bills would cost only 1/2 per cent, whereas those of other states would cost 10 or 12 times as much" (!!), "preference would be given to the former— everybody would be interested in using this money in their payments" (!!!) (p. 274). In order to have more French banknotes, the foreign producers would lower the prices of their commodities and our imports would rise. Since, however, foreign countries can neither buy French annuities with the exported banknotes, or lend them to us again, nor take up mortgages on our land, this import cannot harm us; "on the contrary, it is not we who would have to moderate our purchases, it would be up to the foreign countries to be cautious about their sales" (!!) (pp. 274-75).

Owing to the influx of these miraculous French banknotes foreign countries would be compelled to repeat the same economic revolution which Proudhon has achieved for France.

Finally, an appeal to the Republican lawyers, Crémieux, Marie, Ledru, Michel, etc., to take up these ideas. They, the representatives of the idea of justice, are called upon to pave the way here (pp. 275, 276).

Seventh Essay

"THE MERGING OF GOVERNMENT IN THE ECONOMIC ORGANISM"

1. "Society without authority"

Rhetoric.

2. "Elimination of governmental functions. Cults"

Historical, religious philosophical fantasies. Result: this aspect of the voluntary system[zd] that prevails in America amounts to the abolition of the state (pp. 293-95).

3. "Justice"

No one has the right to judge another unless the latter makes him his judge and freely consents to the law that he has transgressed ...

and other such profound observations.

Under the "regime of contract", everyone has given his consent to the law, and "in accordance with the democratic principle, the judge must be elected by those who are justifiable"

(this is the case in America).

In cases of common law the parties should choose arbitrators whose judgment has executive force in all cases. Thus the state is eliminated also from the judicature (pp. 301-02).

4. "Administration, police"

Where all stand in contractual relations to all, no police is necessary, "and the citizens and communes"

(hence also the departments and therefore also the nations)

"no longer need the intervention of the state to manage their property, to construct their bridges, etc., and to carry out all acts of inspection, preservation, and policing" (p. 311)

In other words, administration is not abolished but merely decentralised.

5. "Public education, public works, agriculture, commerce, and finance"

All these Ministries will be abolished. Fathers of families elect the teachers. The teachers elect the higher educational authorities right up to the supreme "Academic Council" (p. 317). Higher, theoretical education will be linked with vocational education; so long as it is divorced from apprenticeship it is aristocratic by nature, and serves to strengthen the ruling class and the power it wields over the oppressed (pp. 318-19).

On the whole, this, too, is very narrowly conceived and bound up with the division of labour, exactly as is apprenticeship in the workers' companies.

Incidentally, "I do not see any harm in the existence of a central research department, and a department of manufactures and arts in-the Republic".

Merely, the Ministries and the French system of centralisation have to be done away with (p. 319).

There must not be any Ministry of Public Works because it would preclude the initiative of the communes and departments, and of the workers' companies.

Therefore here, too, we have the Anglo-American system with social embellishments (pp. 320-21).

The Ministry of Agriculture and Trade is sheer parasitism and corruption. The proof: its budget (pp. 322-24).

The Ministry of Finance comes to an end of itself when there are no longer any finances that have to be administered (p. 324).

6. "Foreign affairs, war, the navy"

Foreign affairs will cease to exist in view of the inevitable universal character of the revolution. The nations will become decentralised, and their various sections will carry on intercourse with their neighbours as if they belonged to the same nation. Diplomacy and war will be at an end. If Russia wants to interfere, Russia will be revolutionised. If England is not willing to give in, then England will be revolutionised and there is an end of the difficulty. The revolutionised nations have the same interests because political economy, like geometry, is the same in all countries. "There is no Russian, English, Austrian, Tartar or Hindu economics, any more than there is a Hungarian, German or American physics or geometry" (p. 328).

"Epilogue"

Pure rhetoric. In between is the following point-blank shot which, rather amusingly, overthrows the whole edifice of anarchy.

In the economic regime, "reason aided by experience reveals to man the laws of nature and society, and then it tells him: These laws are those of necessity itself, no man has made them, no one imposes them on you.... Do you promise to respect the honour, the liberty and the well-being of your brothers? Do you promise never to appropriate the products or property of another, whether by violence or fraud, usury or stock-jobbing? Do you promise never to lie or deceive, whether in matters of law or commerce, or in any of your transactions? You are free to accept or refuse. If you refuse, you belong to the society of savages; expelled from the community of the human race, you become a suspect; you have no protection. At the least insult, anyone can strike you without incurring any other charge than that of ill-treatment needlessly inflicted on a beast. If, on the other hand, you swear adherence to the pact, you belong to the society of free men. All your brothers pledge themselves with you, promise you loyalty, friendship, assistance, service, exchange. In case of infringement, on their part or yours, by negligence, passion or malice, you are responsible to one another for the harm done, as also for the disgrace and insecurity of which you will have been the cause; this responsibility, taking into account the seriousness of perjury or repetition of the offence, can go as far as to incur excommunication or death" (pp. 342-43).

There follows the wording of the oath of the new alliance, sworn

"On one's conscience, before one's brothers, and before humanity".

Finally, reflections on the present state of affairs.

The peasant has no politics, the worker ditto, but both are revolutionary. Like them, the bourgeois minds his interests, and hardly worries about the form of government. He naively calls that "being conservative and not at all revolutionary". "The merchant, the industrialist, the manufacturer, the landowner ... these people want to live and to live well; they are revolutionary to their heart's core, only they seek the revolution under a false banner." Moreover, they have been frightened by the - necessity that at the beginning the revolution had to take up a position corresponding to "the special point of view of the proletariat"; "today the question has been too clearly elucidated for such a split"

(between bourgeoisie and proletariat)

"to continue any longer" (p. 347). With credit and interest at 1/4 per cent, the bourgeoisie will become revolutionary, this does not frighten them.

Final rhetoric addressed to Cavaignac and Ledru-Rollin:

When they say that "the republic stands above universal suffrage", that means: "the revolution stands above the republic"[359]

|

Written in August and October 1851

First published in Russian in Marx-Engels Archives, Vol. X, 1948 Printed according to the manuscript Translated from the German and the French Published in English for the first time |

Notes

[a] The French Revolution.—Ed.[b] The day Louis XVI was executed after the Convention had sentenced him to death.—Ed.

[c] Engels uses the English word.—Ed.

[d] 1848.—Ed.

[e] Engels has "l'idée gouvernementale", Proudhon "le préjugé gouvernemental"[343][343] (p. 40).—Ed.

[f] A pun in the original: Proudhon has "contrepoids" (counterpoise), Engels has "contre quoi" (against what).—Ed.

[g] Proudhon has "l'ordre dans une société" (p. 43).—Ed.

[h] Engels uses the English word.—Ed.

[i] Proudhon has said earlier: "la concurrence [doit] servir à garantir la sincérité du commerce" ("competition [must] serve as a guarantee of honesty in commerce").—Ed.

[j] Toad, contemptible person.—Ed.

[k] Here and below Engels uses the English term.—Ed.

[l] Proudhon has: "des classes laborieuses" (p. 63).—Ed.

[m] Such is the trenchant logic of M. Proudhon.—Ed.

[n] One can say.—Ed.

[o] Proudhon has: "the legislator of 1789" (p. 66).—Ed.

[p] Proudhon mistakenly has: "de nihilo"—"without ground", "without reason" p. 87). Engels queries this and suggests "ex [nihilo]"—"out of nothing".—Ed.

[q] Engels uses the English term.—Ed.

[r] "From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs", L. Blanc, "Un homme et une doctrine", Le Nouveau Monde, No. 6, December 15, 1849.—Ed.

[s] Proudhon has: "Louis Blanc considered himself the bee of the revolution, but was merely its cicada" ("Il s'est cru l'abeille de la révolution, il n'en a été que la cigale").—Ed.

[t] Engels' quotation marks.—Ed.

[u] Engels uses the English word.—Ed.

[v] That of 1789-94.—Ed.

[w] See this volume, p. 559.—Ed.

[x] Proudhon deals with landed property here.—Ed.

[y] Proudhon has: "se soumet à la loi de la concurrence" ("submits itself to the law of competition") (p. 256).—Ed.

[z] You know them very well, M. Proudhon.—Ed.

[za] Engels uses the English term.—Ed.

[zb] Engels wrote this sentence in English.—Ed.

[zc] Proudhon has: "8 days, 15 days, one month, three months, depending on the importance of the contract" (p. 269).—Ed.

[zd] Engels uses the English term.—Ed.

[337] This review of Proudhon's book, Idée générale de la Révolution au XIX-e siècle (1851), containing many critical remarks, was written by Engels at the request of Marx who had decided to write a polemical work against Proudhon. In August 1851 Marx and Engels discussed Proudhon's book in many of their letters. In his letter to Engels of August 8 Marx gave a detailed account of its contents, citing large excerpts, and in mid-August he sent the book to Engels in Manchester asking him for a detailed opinion on it. Engels worked on the review in August (from about August 16 to 21) and from mid-October, and returned it to Marx at the end of October. On November 24, 1851 Marx wrote to Engels: "I have been through your critique again. It's a pity qu'il n'y a pas moyen [that there's no means] of getting it printed. Otherwise—and if my own twaddle were added to it—we could bring it out under both our names, provided this didn't upset your firm in any way" (see present edition, Vol. 38).

When Marx learned that Joseph Weydemeyer (who had emigrated to the United States in the autumn of 1851) was going to publish the weekly Die Revolution in New York beginning in January 1852, he decided to publish the critique of Proudhon in that journal. On December 19, 1851 he asked Weydemeyer to publish in his weekly an announcement of the forthcoming publication of the Neuste Offenbarungen des Sozialismus oder "Idée générale de la Révolution au XIX-e siècle, par P. J. Proudhon." Kritik von K. M. in the form of a series of articles. In January 1852 the notice was published in the first issue of Die Revolution, but the plan did not materialise. Until April 1852 Marx was engrossed in writing The Éighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. By that time Die Revolution had already ceased to exist as a periodical due to the editor's lack of funds.

In this volume excerpts from Proudhon's book are printed in small type, literal quotations being given in quotes while Engels' expositions of Proudhon's text in German are not. Engels' own text is in ordinary type and the emphasised words are italicised. The French quotations and the German text are translated into English; the French words and expressions used by Engels in his own text are reproduced in the original and supplied, whenever necessary, with translations in footnotes. Editorial insertions in square brackets are made only when there are obvious omissions in the text or when it is advisable to give Proudhon's terms in French besides their English translations. In the small-type text the words in ordinary italics are ones emphasised by Proudhon, those in heavy italics by Engels.

[338] États généraux (States-General) —in feudal France the supreme consultative body composed of representatives of the various estates. From 1614 they did not meet until 1789, when they proclaimed themselves the National Assembly.

[339] Proudhon here refers to a series of trials in 1822 of members of republican societies (including carbonari) who tried to foment anti-monarchist uprisings in Belfort, La Rochelle and Saumur, and to an uprising on May 12, 1839 in Paris. The May uprising, in which revolutionary workers played the leading part, was prepared by the secret republican-socialist Society of the Seasons led by Auguste Blanqui and Armand Barbès, it was suppressed by troops and the National Guard.

[340] The new electoral law which in fact abolished universal suffrage in France was adopted by the Legislative Assembly on May 31, 1850 (see this volume, p. 145, where Marx characterises this law).

[341] In May 1852 Louis Bonaparte's term of office as President expired. Under the French Constitution of 1848, presidential elections were to be held every four years on the second Sunday in May, and the outgoing President could not stand for re-election.

[342] During the night of August 3, 1789 the French Constituent Assembly, under pressure from the growing peasant movement, announced the abrogation of a number of feudal obligations which had already been abolished by the insurgent peasants.

[343] Here and below Proudhon uses the terms le préjugé gouvernemental, le système gouvernemental and l'évolution gouvernementale to denote different aspects of the political system of government to which he counterposes the economic system, organisation of economic forces, invented and proposed by himself.

[344] According to a medieval tradition which even the French Revolution was unable to do away with, the sale of meat in Paris was in the hands of a butchers' corporation that maintained low prices on livestock and high prices on meat. When speaking of "the sale of meat by auction" (le vente de la viande à la criée), Proudhon had in mind a series of measures carried out by the government from 1848 to liquidate the monopoly of the butchers' corporation (authorisation of daily trade in meat by people who did not belong to the corporation, etc.).

[345] Proudhon further discloses the meaning of the term "parasitism": "Parasitism is finance, abusive property, the budget and all that accompanies it" (pp. 51-52).

[346] Royer-Collard made this speech on January 22, 1822, when an anti-press bill was being debated in the Chamber of Deputies.

[347] The parliaments in France —judicial institutions that came into being in the Middle Ages. The Paris parliament was the highest court of appeal and also performed important administrative and political functions, such as the registration of royal decrees, without which they had no legal force. The parliaments enjoyed the right to remonstrate against government decrees. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries they consisted of officials of high birth called the "nobility of the mantle". The parliaments ultimately became the bulwark of Right-wing opposition to absolutism and impeded the implementation of even moderate reforms, and were abolished during the French Revolution, in 1790.

[348] The reference is to the Charte octroyée granted in 1814 by Louis XVIII. It was the fundamental law of the Bourbons, introducing a regime of moderate constitutional monarchy with wide powers for the king and high electoral qualifications ensuring above all political privileges for the landed aristocracy.

[349] Proudhon goes on explaining his idea: "...This principle which is of all importance in the so-called butchers' associations has so little in common with the essence of the association that in many of these slaughter-houses the work is done by hired workers under the guidance of the director who represents the depositors."

[350] Engels refers to the following footnote by Proudhon on pp. 97 and 98 of the book in question: "Reciprocity is not identical with exchange; meanwhile it increasingly tends to become the law of exchange and to mix up with it. A scientific analysis of this law was first given in a pamphlet, Organisation du crédit et de la circulation (Paris, 1848, Garnier frères), and the first attempt to apply it was made by the People's Bank"

The People's Bank (La Banque du Peuple) was founded by Proudhon in 1849 to implement the reforms he suggested in the sphere of credit and circulation which he saw as a means of solving the social question and establishing class harmony. By means of these reforms Proudhon hoped to liquidate loan-interest and to organise exchange without money while preserving private property in the means of production and the wages system. According to Proudhon, this peaceful process was to transform capitalism into a system of equality under which every member of society could become a free producer and exchange equal quantities of labour with others. The short-lived People's Bank only showed how groundless were Proudhon's projects both in theory and in practice.

[351] Engels refers here to workers' associations permissible in Proudhon's system. While stressing the need for a reform in the sphere of credit and money circulation and for the maintenance of individual property in the means of production, Proudhon also admitted the need for the transfer of a number of big factories, railways, mines; etc., to associations of workers employed in them. Accordingly, Proudhon's term compagnies ouvrières is further translated as "workers' associations".

[352] The Historical School of Law —a trend in German historiography and jurispru¬dence which emerged in the late eighteenth century. The representatives of this school—Gustav Hugo, Friedrich Karl Savigny and others—sought to justify feudal institutions and the privileges of the nobility on the grounds of the inviolability of historical tradition.

For a criticism of this trend see Marx's works: The Philosophical Manifesto of the Historical School of Law and Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Law. Introduction (present edition, Vols. 1 and 3).

Legitimists—supporters of the Bourbon dynasty, which represented the interests of the big hereditary landowners. By the "first generation of French Legitimists" Engels means royalist writers and politicians who were vehemently hostile to the French Revolution, being particularly outraged when, in 1792, the monarchy was overthrown. After the restoration of the Bourbons, in 1815-30, the Legitimists formed a Right-wing political party which continued to be active even after 1830, when the dynasty was overthrown a second time.

[353] The reference is to the Constituent National Assembly which held its sessions from May 4, 1848, and to the Legislative National Assembly which replaced it on May 28, 1849. Louis Bonaparte was elected President of the French Republic by universal suffrage on May 10, 1848. p. 558

[354] The Jacobin Constitution, adopted by the Convention on June 24, 1793, proclaimed the freedom of person, religion, legislative initiative and the press, freedom to present petitions, and the right to work, to education, and to resist oppression while leaving private property intact. The difficult situation in the republic caused by foreign intervention and counter-revolutionary revolts made the Jacobins postpone the implementation of the constitution and temporarily introduce a democratic-revolutionary dictatorship. After the counter- revolutionary coup d'état of the ninth Thermidor (July 27-28), 1794, the Constitution of 1793 was replaced in 1795 by a new qualification and anti-democratic constitution.

[355] The reference is to the Bank of France founded in 1800 by a shareholders' company under Bonaparte's protection. It enjoyed a number of state privileges while remaining the property of the company. In 1848 this bank was granted the monopoly right to issue banknotes of small denomination; its monopoly position was also consolidated by the fact that provincial banks were deprived of the right to issue money.

[356] In his letter to Engels on August 8, 1851, Marx wrote concerning this passage in Proudhon's book: "Instead of interest the state pays annuities, i.e. it repays in yearly quotas the capital it has been loaned" (see present edition, Vol. 38).

[357] In accordance with the Constituent Assembly's decrees of January 15 and February 16 and 26, 1790, a new administrative division was introduced in France: the country was divided into 83 departments which, in their turn, were subdivided into cantons and the latter into communes.

[358] Among the socialists Proudhon names Saint-Simon, Fourier, Owen, Cabet, Louis Blanc, and the Chartists.

[359]

The beginning of Chapter One of Pushkin's novel in verse Yevgeny Onegin is reproduced on the last page of Engels' manuscript. It corresponds to the Russian original though it is written in Latin letters. This is apparently connected with Engels' study of the Russian language which he began in Manchester in 1851 (see illustration between pages 564 and 565 in this volume).

MarxEngles.public-archive.net #ME1864en.html